As an immigrant, I initially binged Norwegian literature to learn more of the language and the culture of my new home, but it soon felt more like an escapist pastime. Racism clouded most of my off-the-page interactions until I forged relationships with BIPOC Norwegians who empathized and shared their strategies.

In my novella Sita in Exile, set in the contemporary Norwegian Arctic, the protagonist’s preferred escape route isn’t fiction, but Hindu mythology. Sita, a newlywed desi copywriter from the Chicago suburbs, has followed in her mother’s footsteps in a way neither of them would have expected: just as her then-newlywed mother accompanied her husband from India to the United States decades ago, Sita’s married her boyfriend of not-quite-a-year and followed him to a small Norwegian town where the pandemic hasn’t quite frozen the economy. As Sita struggles to keep her grip on her relationship and on reality itself, she is buoyed by the women of color in her life: Bhoomija, a fellow American desi trying to make it as an artist in New York, and Mona, a second-generation Norwegian balancing the demands of parenthood with her goal of becoming a competitive surfer.

Sita in Exile is shaped by the Norwegian classics—like Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, with its own protagonist-in-exile—but also heavily influenced by the work of other BIPOC Norwegian novelists. Approximately 10% of the country is of Indigenous or minority background, and while BIPOC Norwegian writing is plentiful, English translations can be hard to come by. Here are 10 of my favorite BIPOC Norwegian novels with English translations, or, at a minimum, with translated English excerpts:

Pakkis by Khalid Hussain, translated by Ingeborg Kongslien and Claudia Berguson

Sajjad, a Pakistani Norwegian teenager, struggles to create and live by his own value system while navigating the clash between his religious immigrant parents’ dreams and social pressure to prioritize football, parties, and the white gaze. Pakkis, first published in 1986, when Hussain was himself a teenager, was the first Norwegian-language novel by a non-white author, and this spare, earnest coming of age story is now considered a modern classic.

The Most Beautiful Dawn by Elle Márjá Vars, translated by Laura A. Janda

Sami novelists have been publishing since before Norway’s independence in 1905. In this coming-of-age story, Lina, a 15-year-old girl struggling with dyslexia in the Norwegian far north, only manages to get through school by nursing crushes on student council president Ailu and soccer star Larin. But when she’s with Zlatan, an older man who lives in the forest and fosters her talent for traditional Sami art, life itself seems not only bearable but real. Vars’ debut Katja, translated into Norwegian from Northern Sami in 1988, is considered canon. Katja evokes the visceral sorrows of its eponymous protagonist’s boarding school experience and post-graduation navigation of non-Sami society. Lina’s story in The Most Beautiful Dawn is less bleak but no less effervescent.

Mottak by Nathan Haddish Mogos

Mogos drew upon his own experiences of asylum center life in northern Norway for his debut novel. As the government struggles to determine whether he is Ethiopian or Eritrean, an unnamed protagonist lives in a suspended state. He whiles away the hours either in banter with his friends or in arguments with the refugees from other regions, punctuating an existence that feels increasingly meaningless with all the trappings of masculinity and an uncertain future. As in Mogos’ most recent novel, the Eritrea-set Amid the Chaos, the young men in Mottak (the Norwegian word for reception, as in Reception Center) luxuriate in their discussion, making it both easy and impossible to ignore the surrounding despair.

Black Sky, Black Sea by Izzet Celasin, translated by Charlotte Barslund

When Oak, a naïve aspiring poet, joins protests in 1970s Taksim Square, he meets Zuhal, a committed revolutionary whose magnetism almost sways him from his pacifism. Although Oak attempts to live an apolitical life, thoughts of Zuhal’s glittering ideology—and glittering eyes—refuse to slip away. As Oak continues down his own more pedestrian path in Turkey’s politically turbulent 1980s, he is always cognizant of the alternate path of armed resistance and the allure it can have. Celasin, a political refugee who came to Norway from Turkey in the late 1980s, deftly weaves domestic scenes with dramatic moments.

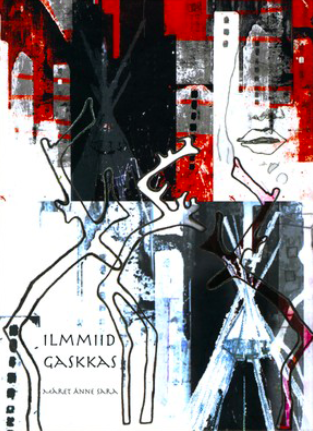

In Between Worlds by Máret Anne Sara, translated by Laura A. Janda

After his father yells about the destruction of the reindeer’s traditional grazing fields because of the construction of a new dirtbike path, teenage Lemme and his sister Sánne take Lemme’s dirtbike and disappear. As their parents search for them, the siblings have transformed into reindeer, and they will have to look to the natural world and the old stories for guidance.

Don’t Run, My Love by Easterine Kire

Atuonuo is proud of her mother, who lives on her own terms rather than by the rules the village elders would impose on a widow. When the charismatic Kevi proposes, Atuonuo is besotted, but hesitant to tie herself to a man so young. Kevi’s turn to aggression is quick, harsh, and lyrically wrought, and she must accept help from both her mother and the village elders to survive the beastly onslaught. Kire, who immigrated to Norway from India as an adult, is known for her translations from both Norwegian and the North-East Indian language Tenydie, as well as for her own English-language poetry and prose infused with the folklore of Nagaland.

The Weather Changed, Summer Came and So On by Pedro Carmona-Alvarez, translated by Diane Oatley

After a tragic loss, Johnny follows his wife, Kari, from the United States back to her native Norway. Centered on Johnny’s grief, his dislocation, and his relationship with his daughter Marita, the prose of this novel echoes the language of grief as it cracks and compels. Chilean Norwegian author Carmona-Alvarez’s background as a musician is clear here and in the novel’s sequel, Bergen Youth Theatre, which follows Marita into her adolescence.

The Yellow Book by Zeshan Shakar, translated by Kari Dickson

The entire Oslo Trilogy is worth reading (here’s an excerpt from the hilarious first book, Our Street, translated by David M. Smith), but its second volume, The Yellow Book, makes full use of the indefatigable warmth of Shakar’s prose.

Norwegian Pakistani Mani has made it… kind of. His top-notch degree hasn’t netted him an international consultancy job that would reassure his anxious father or his girlfriend, Meena. Instead, he finds himself settling into a government job at the Ministry of Education. It provides the possibility of belonging to something ambitious, positive, and—put in the diplomatic jargon of his new life—mainstream, if he can just maintain his focus. Shakar’s light touch brings levity to a novel about a young, brown man living in Oslo during the 2011 terrorist attacks.

Emily Forever by Maria Navarro Skaranger, translated by Martin Aitken

Navarro Skaranger’s debut novel All Foreigners Keep Their Curtains Closed delved into the life of a teenage girl in a predominantly ethnic minority suburb of Oslo. The 2020 film adaptation is currently available to stream on Netflix.

Her latest book Emily Forever presents its young, pregnant, working-class protagonist through a kaleidoscope. The sharpness of the details describing Emily’s changing life are softly satirical—chosen, it feels, to match those that would delight a newspaper reporter penning their first expose about multiculturalism—and her dulled responses leave her something of an enigma. A quietly rebellious novel that sees Emily through the lens of others, the 19-year-old expectant mother refuses to grasp for something to make meaning of her life, stubbornly defying societal expectations.

The Thinnai by Ari Gautier, translated by Blake Smith

In a working-class neighborhood of Pondicherry, Gilbert, an old Frenchman, settles himself on a local’s thinnai (veranda) and spins a tale about a mysterious diamond his family has been guarding for generations. Is Gilbert merely a loquacious holdover from Pondicherry’s days as a French outpost, or does he have a new con in mind? This is a picaresque written originally in French; Gautier is an Indo-Malagasy writer who immigrated to Norway as an adult and grew up amongst the communists, the missionaries, and the market stall women he paints so vibrantly in the novel.