My family immigrated to the U.S. from the former Soviet Union as political refugees when I was two years old. We left the only home my parents had known—the country where my great-grandfather was murdered as an enemy of the state, where my father had to join the army to “earn” one of the few medical school spots open to Jews, where my grandfather had to bribe a government official for me to be named Ruth (it wasn’t an option in the Soviet book of names). Having grown up under much more stable conditions in Los Angeles, these stories are unrelatable to me. But this legacy is a weight I carry at all times. Intergenerational trauma is, by nature, a form of collateral damage. Though I can’t distill down into a pithy thesis how this inheritance has shaped me, I know with certainty that it has. The sense that I owe my ancestors an unrepayable debt for their sacrifices, my choice of a “stable” day job as a pharmacist, my often boundaryless relationship with my family—all feel connected to what my relatives survived, and what they didn’t survive.

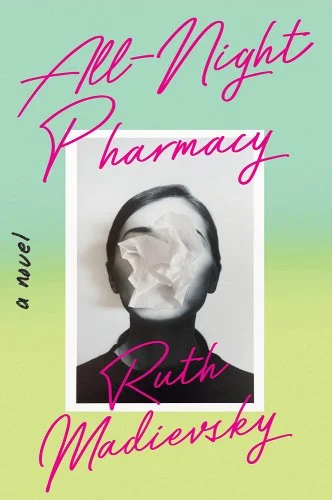

My debut novel, All-Night Pharmacy, tracks the coming-of-age of a young woman in a toxic entanglement with her larger-than-life older sister, Debbie. A wild night of taking mystery pills at their beloved dive bar turns violent, and Debbie vanishes without a trace. Our unnamed narrator, who has always defined herself in relation to Debbie, finds herself consumed with unease over what kind of person to be. That’s when she falls under the wing of an alluring Soviet Jewish refugee, Sasha, who claims to be a psychic tasked with acting as her spiritual guide. The narrator, like Sasha, is of Soviet Jewish descent, albeit several generations ago. Despite growing up in America to American-born parents, our narrator senses that the horror her ancestors experienced continues to pull the strings of her own life.

This reading list features seven books that respect the mystery and nuance of intergenerational trauma and its aftermath. Like my novel, these books reckon with family legacies atmospherically. The weight of that inheritance doesn’t hit these characters like a truck. It’s a mist that settles over them. Even when they can’t see it, it’s in the air they breathe. And lest you think these books—mine included—sound depressing as hell: I promise you’re in for a wild ride full of hot bathtub sex in a former Soviet republic, literal treasure hunts, and laugh-out-loud dark comedy.

Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure by Menachem Kaiser

Plunder is a wild journey into the dark heart of post-Holocaust Eastern Europe. Menachem Kaiser takes up his Holocaust-survivor grandfather’s twenty-year failed attempt to reclaim the Polish apartment complex stolen from his family by Nazis. With the help of a Polish lawyer nicknamed “The Killer” and her translator daughter, Kaiser navigates the bureaucracy of the Polish legal system and his own thorny feelings about what taking back the long-lost building would mean for its current residents. Along the way, he discovers that a Holocaust survivor relative has written a memoir with a cult following, and explores a secret network of underground Nazi tunnels with a ramshackle crew of treasure hunters, among other chaotic adventures. Kaiser’s thoughtful consideration of the allure of Nazi conspiracy theories (“World War II is psychically a lot easier when it’s about antigravity and time travel than when it’s about gas chambers and stacks of corpses.”) helped me subtly put into words how Soviet Jewish trauma shaped my narrator’s family. The memoir wraps up with a page-turning treasure hunt where family lore, true crime, and the occult collide.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti

The narrator of Motherhood attempts to decide through a series of experiments whether to have a child before her fertility window closes. The beautiful weirdness of Heti’s mind is on full display in this book, which feels like an invented novel form of its own. The narrator circles her complex feelings about motherhood through a self-devised occult practice, inspired by the I Ching, in which she flips three coins to answer yes-or-no questions. Her approaches to the motherhood question are innovative and hilarious: “When I was younger, thinking about whether I wanted children, I always came back to this formula: if no one had told me anything about the world, I would have invented boyfriends. I would have invented sex, friendship, art. I would not have invented child-rearing.” She considers whether having a child means honoring her own mother, and whether it could be a way to turn her mother’s “sadness into gold.” One anecdote is especially haunting: a Jewish woman attempts to track down why each generation of women in her family cooks chicken by first tying its legs together in the pot. Her mother answers, “That’s the way my mother did it,” as does her grandmother. Finally, her great-grandmother explains, “That’s the only way it would fit in my pot.” Heti concludes that this “is how childbearing feels to me: a once-necessary, now sentimental gesture.” And then she proceeds to vacillate in consistently surprising ways for another 250 pages.

The Four Humors by Mina Seçkin

My copy of The Four Humors looks like a middle-schooler’s science textbook the day before the final exam: underlined and dog-eared and sticky-noted within an inch of its life. The novel follows college student Sibel as she spends the summer in Istanbul with her grandmother and white American boyfriend (who the Turkish community seem to prefer to her—brutal!). Instead of preparing for the LSAT, Sibel spends her days avoiding her father’s grave, eating fragrant meats, and using the four humors theory of ancient medicine to treat her mysterious chronic headache. The Four Humors puts the “literary” in literary fiction, full of razor-sharp sentences like, “She picks at my mispronounced vowels like at the white flesh on a fish bone.” I nearly passed out at her description of Turkish talk shows that spew pseudoscientific diet advice and air out dirty family laundry for how uncannily similar it was to the toxic Russian talk shows I describe in my novel. “Is every immigrant culture the same??” I frantically texted several friends along with a link to the book. The Four Humors astutely and entertainingly observes the aftermath of family secrets and political violence on multiple generations of a millennial slacker’s family.

Heavy by Kiese Laymon

Laymon’s memoir takes the form of a letter to his mother, a gifted academic who physically abused Laymon to steel him against the more violent—perhaps fatal—assaults of life as a Black man in America. Heavy reckons with his family legacy of sexual trauma, disordered eating, and his own propensity for cruelty; Laymon doesn’t dish anything he can’t take. As a stylist, he recounts systemic and interpersonal assaults—including being abused by his babysitter and being expelled from Millsaps College for not signing out a library book—with cutting tenderness. His interrogation of self, of his family, and of America sinks in as smoothly as a freshly sharpened knife: “America seems filled with violent people who like causing people pain but hate when those people tell them that pain hurts.” I cringe when any book is described as “brave” (it’s the touch of condescension for me). But Heavy is not a book that I’d have the guts to write, and I don’t know that even twenty more years of therapy would make it so. How lucky we are that Laymon found the words for what “my body knew” but “my mouth and my mind couldn’t, or maybe wouldn’t, express.”

Oksana, Behave! by Maria Kuznetsova

I laughed, I cried, I laugh-cried. This novel-in-stories follows Soviet Jewish immigrant Oksana from childhood to early adulthood as she navigates life across America with her striver parents and—here’s a term I don’t use often—her horny grandmother. One storyline in particular, which tracks her father’s path from delivering pizza as a new immigrant, to working at Goldman Sachs, to a tragic accident in the luxury car that symbolized his attainment (finally!) of the American dream, absolutely wrecked me. Kuznetsova’s dark humor is distinctly Soviet Jewish. While staring at a photograph of her grandfather “for signs that he would die soon,” Oksana “screamed…but nothing happened, nobody came, not the regular police or the secret police.” Her new American friends have hair “as black and shiny as the trash bags where Mama kept my old clothes.” Oksana, Behave! masterfully depicts the chaos of young adulthood, the diasporic loneliness of living between worlds, and the grief of wondering what could have been had you never immigrated at all.

Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

Vuong’s debut poetry collection is a compulsively underlinable reckoning with queerness, immigration, familial trauma, and the legacy of the Vietnam war. His poems teem with arresting imagery: “the chief of police / facedown in a pool of Coca-Cola. / A palm-sized photo of his father soaking / beside his left ear.”; “apples thunder / the earth with red hooves”; “I pretend…that you’re not saying / my name & it’s not coming out / like a slaughterhouse.” Vuong’s lyrics have a shocking musicality; he lushly describes terrible violence without glorifying it. His poems can also be very funny, as when he writes, “Note to self: If Orpheus were a woman I wouldn’t be stuck down here.” These are poems of familial love and resentment and every shade of pain and passion in between. Despite Night Sky with Exit Wounds’ melancholia, it makes for charismatic and unforgettable company.

Without Protection by Gala Mukomolova

This debut poetry collection’s dedication—“For all my relations, especially my father, who walked me toward this book and will never set a living eye upon it”—gives you a sense of the lyric exploration of grief and family legacy to come. Mukomolova’s poems depict the raw sensuality and horror of young adulthood, of coming into one’s queerness, of becoming disillusioned to the world’s cruelty. The Russian folk tale of Vasilyssa the Beautiful, who battles the crone witch Baba Yaga, is a slanted window through which the speaker examines her identity as a queer, Soviet Jewish refugee living in New York. “High school wasn’t always two towers crashing,” opens a stark prose poem about the danger and ecstasy of girlhood amid a backdrop of national tragedy. I would be tempted to describe Mukomolova’s lines as a gut-punch, if they didn’t hurt so good: “Our pinhole cameras reeled us in…In the darkroom, we were the light.”