These 10 books take the imaginability of other minds as their explicit subject. Their writers are curious about nonhuman consciousness: could language reproduce that as well? In order to imagine

what animals, plants, or objects might be thinking, these writers try to think those thoughts themselves. They wonder: what is it like to be an elephant, or a cockroach, or a Joshua tree? What is it like to be a chatbot, or a planet, or a vampire?

In his 1974 essay “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?”, the philosopher Thomas Nagel famously concluded that these questions are unanswerable. Since humans can’t echolocate, in his example, it would be impossible for us to truly imagine or describe a bat’s subjective experience. No matter how much we learn about echolocation—its frequency, its range—we still wouldn’t know what it feels like, inside, to hear a squeak ping back from a moth’s wings. The specific perceptual texture or qualia of bat consciousness—‘what it is like for a bat to be a bat’—will remain forever inaccessible.

These writers each try to project themselves inside similar inaccessibilities. Some study their creatures’ sensory organs, perceptual systems, and Umwelten, translating unfamiliar experiences into human terms. Some adopt a fabulist strategy, writing from nonhuman points of view. Some simply follow their human characters’ obsession with otherness. But all of them use language and imagination to bridge their intersubjective abysses. They engage the Nagelian difficulties.

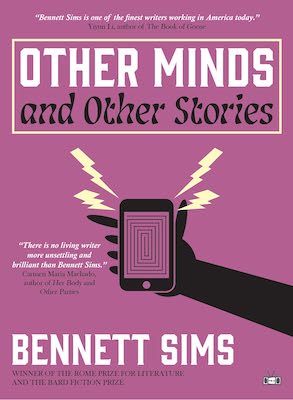

I had this tradition in mind when writing my new book, Other Minds and Other Stories. Throughout the collection, characters project themselves into a variety of perspectives, both human and non-: backyard chickens, Hegel scholars, flakes of snow, amnesiac ghosts, an e-reader’s readers, Pegman from Google Street View. In writing these stories—in imagining what it is like for human characters to imagine what-it-is-likeness—I often revisited these 10 works. They may not teach us, finally, what it is like for a cockroach to be a cockroach. But they reveal how other minds (writers’ minds) have practiced the impossible art of describing other minds.

Exhalation by Ted Chiang

Ted Chiang is best known for “Story of Your Life,” the basis for the film Arrival, and it remains perhaps the best introduction to his work. In its Sapir-Whorf spin on first-contact, a linguist studies an alien species’ language and learns to see the world the way that they do. As she masters their nonlinear writing system, she begins to experience time nonlinearly too, and Chiang is alive as a stylist to the philosophical and poetic challenges of representing a halfway alien mind in a human body.

In Exhalation, Chiang’s new collection, he extends his curiosity about consciousness to a wider variety of creatures: robots; digital pets; parrots; parallel selves. Throughout, he writes with the same rigor about the connection between minds and bodies, the way that perception shapes experience: whether it is the “cognition engine” of a kind of pneumatic robot (“My consciousness could be said to be encoded… in the ever-shifting pattern of air driving these leaves”), or the vocal learning and contact calls of Puerto Rican parrots. As the parrot narrator of “The Great Silence” reminds us, we do not need to make contact with extraterrestrials to communicate with an “alien” intelligence: “We’re a nonhuman species capable of communicating with them. Aren’t we exactly what humans are looking for?”

The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore by Benjamin Hale

Narrated by a hyperintelligent, hyperverbal chimpanzee who has taught himself human language, fallen into forbidden love with his primatologist, and committed murder, The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore reads like Lolita by way of Lincoln Park Zoo. Bruno’s preening erudition, his murderer’s fancy prose style, and his insights into “anthropo-chauvinism” all mark him as the hybrid of Humbert Humbert and Rotpeter, the ape narrator of Kafka’s “A Report To An Academy” (Bruno actually claims Rotpeter as his father, making this novel a semi-sequel to Kafka’s story). Like them, Bruno is at his most charismatic when he’s serving as a funhouse mirror test, reflecting humanity back to his reader all defamiliarized and distorted, and reminding us “how feebly you people know yourselves.” In his autodidactically omnivorous riffs on history and art—touching on everything from Shakespeare to Sesame Street, from Paradise Lost to Pinocchio—he proves that he knows us better: “I am an animal with a human tongue, a human brain, and human desires,” he writes, “the most human among them to be more than what I am.”

Speak by Louisa Hall

Written as a speculative history of AI, Speak features a chorus of human and nonhuman narrators, with historical figures like Alan Turing and a fictionalized Joseph Weizenbaum appearing alongside a chatbot and a robotic doll. In its exploration of language-learning networks and algorithmic intelligence, the novel adopts an algorithmic form, cycling through its six narrators according to the end-word schema of a sestina. Formally inventive, thematically complex, and stylistically daring, Speak suggests that AI is not a new technology at all, but one of our oldest: alongside the diaries and letters that punctuate the novel, the chatbots come to seem like just another writing system. They, too, are a way of preserving absent speakers, transmitting lost voices out of the past and into the present, out of death and into life. This is also, the novel suggests, the function of consciousness itself. When human characters point out to chatbots that they are not “really” thinking—that all they’re doing is recombining received language, echoing others’ minds and others’ voices—the chatbots wonder: isn’t that all that human minds are doing? In the words of one robotic doll: “In the end, I have only their voices… They move through me in currents, on their way somewhere, or perhaps on their way back to the place where they came from.”

The Animal Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder by Patricia Highsmith

In most of Highsmith’s work, the minds she’s interested are human, homicidal ones. Books like The Talented Mr. Ripley and Strangers on a Train explore all the different reasons that people murder one another, and try to get away with murder. But what if Tom Ripley had been a talented rat? In The Animal Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder, Highsmith extends her interest in criminal psychology into the realm of animal cognition, with a series of darkly funny fables about interspecies conflict. An elephant rampages against her sadistic zookeeper. A rat scavenges for scraps in Venice. Debeaked chickens revolt on a barbaric battery farm. Here the great themes of Highsmith’s work—paranoia, panic, resentment, revenge—are recast in an Aesopian mode. Like Noah, she gathers every beast, every creeping thing, and every bird, and shows that they murder for all the same reasons we do. Call it Strangers on an Ark. Yet for all that the collection is not uniformly misanthropic: when one elephant narrator mourns her human zookeeper, she makes an eloquent case for how people might strive to exist with—and write about—animals. “Steve approached me as one creature to another,” she thinks, “making acquaintance with me and not assuming I was going to be what he expected. That is why we got along.”

Bestiary by Donika Kelly

Bestiary’s subject matter is all-too-human trauma: throughout the collection, the speaker confronts childhood memories of her father’s abuse and her own lifelong recovery. But the poems’ methods are zoomorphic. As the speaker processes the past, she finds herself refracted across a prismatic menagerie, including animals (horses, ostriches, bowerbirds); mythological creatures (minotaurs, werewolves, satyrs); and even objects (with poems like “Self-Portrait as a Block of Ice,” “Self-Portrait as a Door,” “Self-Portrait as a Wooden Flower”). There is a sense in which this bestiary can be traced back to a single beast, with all of the collection’s creatures sprouting from a foundational wound (just as Pegasus, the speaker recalls, was “Foaled, fully grown” from a “severed head”). The complexity of the natural world gives form to complicated inner experience. “You’d rather be a simpler animal,” the speaker thinks to herself in one poem. “You try to imagine what the bear feels. / The seal. The otter. Always a little group of three. / You worry they are not, in fact, simpler.”

Solaris by Stanislaw Lem

In Lem’s sci-fi classic, humanity makes contact with an unusual alien intelligence: not sentient beings from another planet, but a sentient planet itself. Astronauts study Solaris from aboard a space station, monitoring the brain-like electrical discharges of its “thinking ocean,” unaware that Solaris is studying them as well. When strange phantoms from their pasts begin materializing onboard, they realize they’re being haunted: not by ghosts, but by memories. Solaris’s telepathic ocean has apparently begun probing their minds, generating “visitors” from their unconscious. The narrator is soon reunited with a visitor of his own: the replica of his dead wife, whose suicide he still blames himself for. But why did Solaris send her? Is the planet punishing him? Studying him via “psychic vivisections”? Giving him a second chance? What does the ocean want? The scientists are as haunted by these questions as by the phantoms themselves, and the novel never does provide any answers. Partly a ghost story, partly a tale of melancholic love, it is also a first-contact novel about non-contact: Solaris’s mind and motives remain unknowable, a planetary reproof to the scientists’ anthropomorphic projections. “Where there are no men,” one scientist warns the others, “there cannot be motives accessible to men.”

The Passion According to G.H. by Clarice Lispector

Alone in her Rio de Janeiro apartment, a sculptor discovers a cockroach. Disgusted, she crushes it, and its bisected shell squirts out white goo like a toothpaste tube. The sight of this paste precipitates a mystical crisis in the narrator, who spends the rest of the novel face to “face” with the dying roach, describing her spiritual transformation in some of the strangest and most visionary language of 20th-century literature. Obsessed with the cockroach’s creatureliness, she comes to understand everything they share in common as living beings: beneath all their differences, they are both made from the same white paste. “The roach with the white matter was looking at me,” as she puts it. “I don’t know what a roach sees… But if its eyes weren’t seeing me, its existence was existing me—in the primary world I had entered, beings existed one another.”

As she blurs all distinctions between creation and creator, cockroach and God, the novel plays out like Kafka’s The Metamorphosis retold on the level of monism. The narrator gradually becomes an insect, not physically, in her body, but metaphysically, in her primary matter. She grows a cockroach soul. Reading G.H., you follow the narrator’s logic to its most physically and philosophically shocking conclusions. You, too, learn to “want the God in whatever comes out of the roach’s belly.”

The Intelligence of Flowers by Maurice Maeterlinck

Like Maeterlinck’s other essays on nonhuman intelligence—The Life of the Bee; The Life of the Ant; The Life of the Termite: bestsellers in their day, now all, unfortunately, out of print—The Intelligence of Flowers admonishes anthropocentrism by highlighting the “genius” of another species. Unembarrassed to describe plants in terms of their minds, their foresight, and their imagination, Maeterlinck celebrates various innovations in the field of “floral mechanics”: from the “Archimedean screw” of the medic seed to the “Machiavellian” pollen traps of the orchid, which “knows and exploits the passions” of the bees who crawl through it. In Maeterlinck’s lush Proustian descriptions of vegetable cunning—which would go on to influence Proust’s own botanical imagery, particularly the famous orchid passage in Sodom and Gomorrah—such evolutionary developments come to seem as full of psychological suspense as any novel. Indeed, for Maeterlinck every plant participates in an essentially tragic drama, resisting its destiny by overcoming immobility: “to escape above ground from the fatality below; to elude and transgress the dark and weighty law, to free itself, to break the narrow sphere, to invent or invoke wings, to escape as far as possible, to conquer the space wherein fate encloses it, to approach another kingdom, to enter a moving, animated world.”

Orange World and Other Stories by Karen Russell

Karen Russell’s otherworldly imagination has always also been an other-mindly one. Throughout her career, her high-concept stories have frequently featured fantastical perspectives, including those of girls raised by wolves, lemon-sucking vampires, human-silkworm hybrids, and US Presidents reincarnated as horses. Orange World, her latest collection, deepens her fascination with the non- and more-than-human, as she turns her limitless gifts for sensory description and figurative language toward figuring out what even weirder creatures might be thinking. These include: a breast-feeding devil; a mummified bog girl; Madame Bovary’s greyhound; and a Joshua tree mind trapped inside a human body. In “The Gondoliers,” Russell even picks up Nagel’s gauntlet, writing from the point of view of a mutated “bat girl,” who navigates a flooded wasteland via echolocation, and who tells us what it is like: “shapes tighten out of an interior darkness. Edges and densities. Objects sing back at us….Pillars thin as lampposts push fuzzily into our minds.”

(Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film by Jalal Toufic

An artist, filmmaker, and theorist of undeath, Toufic approaches the question “What is it like to be undead?” by watching classic vampire movies. Studying the editing techniques and special effects that they employ for vampiric powers—jump cuts for teleportation; matting for hypnosis; voice-overs for telepathy—Toufic attempts to map the labyrinthine underworld of the undeath realm. But when he notices these same editing techniques in non-vampire movies, he reaches a counterintuitive conclusion: these characters must secretly be undead as well (in this way he persuasively, paranoically expands the vampire canon, to include everything from the Marx Brothers to Maya Deren). Things get stranger when Toufic notices undeath’s “special effects” in his own life: after all, “the lapses in epilepsy, hypnosis, schizophrenia, LSD trips, and undeath permit editing in reality.” Dedicated “In memory of the amnesiac Jalal Toufic… [who] was/is dead/undead then/now,” the book takes undeath deadly seriously as a framework for understanding limit states of consciousness, what Toufic calls “reality-as-filmic”: those moments when we wonder “Am I dead?” or “Am I in a movie?” (for Toufic these are the same question).

As he accumulates increasingly wide-ranging examples of undeath, and as he writes in an increasingly wide variety of forms (aphorisms, autotheory, diary entries, letters and emails, plays, short stories, photo-essays), undeath emerges as a profound psychological metaphor. It is also a profoundly political one: Toufic writes powerfully about historical trauma in the Middle East, whose military conflicts, postwar amnesia, and urban ruins all resonate with the haunted castles and hypnotic landscapes of his vampire films. Unexpectedly intimate, thought-provoking, and moving, (Vampires) is the unclassifiable masterpiece of an unclassifiable thinker, whose ideas I have vampirized in all my fiction. Along with Toufic’s other books, (Vampires) is available as a free pdf on his website.