Frequency combs – specialized lasers that act like a measuring stick for light – are commonly used to identify unknown molecules in a sample by detecting which frequencies of light they absorb. Despite recent advances, however, the technique still struggles to record spectra on the nanosecond timescale characteristic of many physiochemical and biological processes.

Researchers at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Gaithersbury, Maryland, Toptica Photonics AG and the University of Colorado, Boulder have now addressed this drawback by developing a frequency comb system that can detect specific molecules in a sample every 20 nanoseconds. Their feat means that the technology could be used to resolve intermediate steps in fast-moving processes, such as those occurring in hypersonic jet engines and protein folding.

Detecting molecular fingerprints

In the new work, NIST project leader David Long and colleagues generated two optical frequency combs in the near-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum using electro-optic modulators. They then used these combs as the pump laser for a device known as an optical parametric oscillator which spectrally translates the combs into the mid-infrared. This translation is important because the mid-infrared region is home to so many strong light absorption features (particularly in biomaterials) that it is known as the “fingerprint regionâ€. The combs’ high power and coherence, together with the broad spacing of their frequency “teethâ€, allows these molecular line shapes to be recorded at high speeds.

As well as being highly effective, the new set-up is also relatively simple. “Many other approaches for dual comb spectroscopy in the mid-infrared required two separate combs that have to be tightly locked to one another,†Long explains. “This means a greatly increased experimental complexity. What is more, earlier techniques generally did not have as a high a power or the possibility of tuning the comb spacing to sufficiently large values.â€

This widely-spaced tuning is possible, Long adds, because the new electro-optic comb only has 14 “teethâ€, compared to thousands or even millions for conventional frequency combs. Each tooth thus has a much higher power and is further from the other teeth in frequency, which results in clear, strong signals.

Table-top frequency comb probes protein structures

“The flexibility and simplicity of the new method are two of its major strengths,†he tells Physics World. “As a result, it is applicable to a wide range of measurement targets, including chemical kinetics and dynamics, combustion science, atmospheric chemistry, biology and quantum physics studies.â€

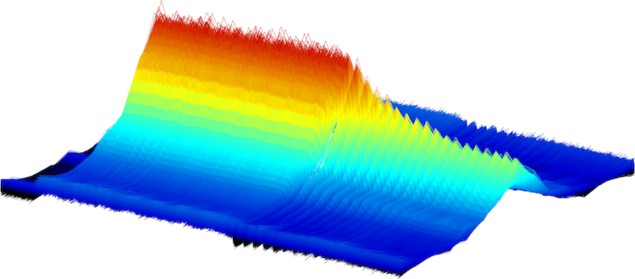

Supersonic CO2 pulses

As a test, the researchers used their setup to measure supersonic pulses of CO2 exiting a small nozzle in an air-filled chamber. They were able to measure the CO2/air mixing ratio and observe how the CO2 interacted with air to create oscillations of air pressure. Such information could be used to better understand processes occurring in aircraft engines and so aid the development of better ones.

As a follow-up to these experiments, which are detailed in Nature Photonics, the researchers say they would now like to study other scientifically interesting chemical systems.